For the first time ever, researchers have tried editing a gene inside the body of a living human patient in a bold attempt to permanently change a person’s DNA to cure a rare genetic disorder called Hunter syndrome. The experiment was carried out on a 44-year-old man, who – through an intravenous (IV) drip – received billions of copies of a corrective gene and a genetic tool that can cut his DNA in a precise spot. Researchers say results come out in three months. And if their experiment does what it’s meant to do, then it would give a major boost to the fledgling field of gene therapy.

Hunter syndrome, also known as mucopolysaccharidosis II (MPS II), is a rare genetic condition that affects approximately 1 in 162,000 live births (most primarily males). It is caused by missing or defective enzyme that’s needed to break down or metabolize some complex molecules. Hunter syndrome progresses over time, and if left untreated, the molecules build up throughout the body in harmful amounts and could lead to chronic and progressive damage that could affect the patient’s physical and mental capacities to varying degrees. There’s no cure for the condition, and most who have it die very young.

This time, the researchers didn’t use CRISPR. Instead, they used a different gene-editing tool called zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). ZFNs are like molecular scissors that seek and cut off a specific part of DNA.

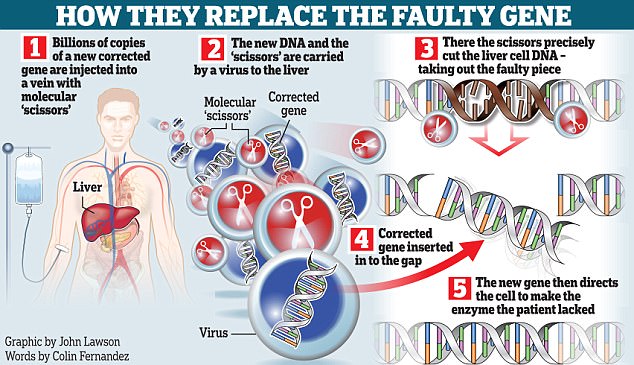

The therapy has three components: the new gene and two zinc finger proteins. DNA instructions telling each component what to do are placed in a virus that’s been modified to not cause infection but to carry them into the patient’s liver cells. Billions of copies of these are inserted through the patient’s vein. They travel to the liver, and the cells then use the instructions to make the zinc fingers and prepare the corrective gene. The fingers cut the DNA, allowing the new functional copy of the gene to slip in. The new gene then directs the cell to make the enzyme that was missing or defective in the patient. For the treatment to be considered successful, only one percent of the patient’s liver cell would have to be corrected.

Researchers working on gene therapy usually alter cells in the lab and return them back to the patient’s body. These are also therapies that don’t involve editing DNA. Moreover, most of these methods are limited to a few types of disease. While some may give results that don’t last, some others may supply a new gene like a spare part but can’t control where it inserts in the DNA, possibly activating a cancer gene. But this time, the genome editing is happening in a precise way inside the body, sending the new gene in exactly the right location.

Source: AP

So wonderful but some religion people condemn. They forget. Jesus healed people physically and spiritually and Luke was a doctor.

LikeLike

Let’s let them do what they wanna do. 😛

LikeLike